When listening with a stethoscope to a patient's heart, one sometimes hears a deviation from the typical "lub-dub" rhythm. Sometimes the "dub" is too loud, or the "lub" too soft. There might be a rubbing sound, or a harsh blowing sound. By interpreting subtle characteristics such as the location, pitch, and timing of these sounds, one can sometimes diagnose things like a diseased heart valve or congestive heart failure. It's very hard to do, and the surest ways to get good at diagnosing heart murmurs are to thoroughly understand the mechanisms of heart disease and to get lots of practice.

Our cardiology professors kindly arranged for me and my medical school classmates to

examine patients with various audible heart abnormalities. We were divided into groups of eight and herded through a series of exam rooms. Three or four of us at a time would place our stethoscopes on each patient's chest, and as a group we tried to diagnose the heart abnormality. One patient had pulmonic valve stenosis, a rare murmur that most physicians will never encounter in their careers. Pulmonic valve stenosis is difficult to differentiate from its oft-encountered cousin, aortic valve stenosis, so finally hearing a patient with the rare pathology was quite useful. Some of the patients had severe disease, with classic physical findings that we've only read about in textbooks. One patient with severe aortic valve stenosis had pulsus tardus et parvus ("diminished and weak pulse"): the feeble pulse I felt in his wrist noticeably lagged behind his heartbeat. Examining these patients helped cement my clinical knowledge.

These patients, most of them elderly, were compensated for letting us examine them. I can't imagine that our examination was fun for them. The patients had to partially disrobe, and some of our stethoscopes probably were cold to the touch. I'd like to think that they came in for reasons besides the pittance they were paid.

Patients seem happy to help us learn, whether it's a couple who lets us examine their newborn or a psychiatric patient who lets us ask deeply personal questions about his life. When I tried drawing blood from one of my first patients, my first two "sticks" were unsuccessful and I informed her that I would get someone more experienced to perform the next attempt. She insisted that I keep trying until I succeeded, because she wanted to help me improve (I thanked her and found the more experienced student anyway).

Two volunteers had had their larynges (plural of "larynx") removed because of cancer caused by smoking. They could breathe only through a hole that had been surgically carved in their necks ("stoma"), and could speak only with the help of assistive devices (which made them sound like Stephen Hawking). They spent an hour with us, taking our questions and letting us try out some of their assisted-speaking equipment. They also taught us some useful clinical pearls: since their mouths are disconnected from their lungs, if they need to be resuscitated, we need to ventilate their necks.

I make sure to thank these patients, and I hope they understand how much they are able to teach us. They have my gratitude.

29 January 2013

19 January 2013

What's wrong?

For whatever reason, some patient visits are more memorable than others. One diagnosis that has stuck in my mind wasn't even a diagnosis.

I asked my patient, "What brings you into clinic today?"

"My urine is dark, even though I've been drinking a lot of water."

Dark urine can be a sign of something ominous, like bladder cancer, or a kidney stone, or an inborn inability to metabolize certain types of protein ("maple syrup urine disease"), or a severe reaction to certain medications and recreational drugs. I started whittling away at my differential diagnosis by asking questions.

"Has your urine looked like it's had blood in it?" "No."

"Does it smell different?" "No."

"How long has this been going on?" "A few days."

"Is your urine brown, like the color of Coca-Cola or maple syrup?" "No."

"Is there pain when you urinate?" "No."

"Are you feeling pain anywhere?" "No."

"Have you noticed any change in your weight?" "No."

"Is there something happening in your life or the life of a loved one that's made you concerned about your health?" "No."

"Have you had vomiting, fever, headache, or any change in bowel habits?" "No."

No red flags. I asked a few more questions, each with an innocuous response. I checked to see if he was tender in his abdomen or his back (which could signal a kidney stone). He was not.

My history and physical exam had turned up nothing suspicious. After consulting with the physician, I ordered a dipstick urinalysis (a quick test for various abnormalities in the urine) and asked the patient to provide a urine sample. After a couple of minutes he returned with his specimen cup. I held it up.

"Is this about as dark as your urine has gotten?" I asked.

"Yes."

"And do you consider this dark?"

"Yeah! I mean, isn't it?"

No. His urine wasn't dark. It was quite pale. And that was the moment that I realized that nothing was wrong with this patient. He didn't need to be in the examination room. He ought to be at home, or at work, or shopping for groceries. Anywhere but here.

I was surprised that I took so long to arrive at this conclusion. But when I had assembled my mental list of potential diagnoses, "nothing" was not among the options I had considered. I had become so accustomed to patients having problems warranting diagnosis and treatment that it had hardly occurred to me that a patient might come in to clinic with nothing the matter.

I was reminded of a time I attended a play, and partway through, the actors "took down the fourth wall" and began speaking directly to the audience. It was a bewildering experience, because all of the sudden, the normal rules of theater did not apply. This patient encounter left me feeling similarly disoriented.

The patient's urinalysis results came back a few minutes later, showing no abnormalities. The doctor and I reassured him that things appeared to be all right, and we sent him on his way.

_______

I asked my patient, "What brings you into clinic today?"

"My urine is dark, even though I've been drinking a lot of water."

Dark urine can be a sign of something ominous, like bladder cancer, or a kidney stone, or an inborn inability to metabolize certain types of protein ("maple syrup urine disease"), or a severe reaction to certain medications and recreational drugs. I started whittling away at my differential diagnosis by asking questions.

"Has your urine looked like it's had blood in it?" "No."

"Does it smell different?" "No."

"How long has this been going on?" "A few days."

"Is your urine brown, like the color of Coca-Cola or maple syrup?" "No."

"Is there pain when you urinate?" "No."

"Are you feeling pain anywhere?" "No."

"Have you noticed any change in your weight?" "No."

"Is there something happening in your life or the life of a loved one that's made you concerned about your health?" "No."

"Have you had vomiting, fever, headache, or any change in bowel habits?" "No."

No red flags. I asked a few more questions, each with an innocuous response. I checked to see if he was tender in his abdomen or his back (which could signal a kidney stone). He was not.

My history and physical exam had turned up nothing suspicious. After consulting with the physician, I ordered a dipstick urinalysis (a quick test for various abnormalities in the urine) and asked the patient to provide a urine sample. After a couple of minutes he returned with his specimen cup. I held it up.

"Is this about as dark as your urine has gotten?" I asked.

"Yes."

"And do you consider this dark?"

"Yeah! I mean, isn't it?"

No. His urine wasn't dark. It was quite pale. And that was the moment that I realized that nothing was wrong with this patient. He didn't need to be in the examination room. He ought to be at home, or at work, or shopping for groceries. Anywhere but here.

I was surprised that I took so long to arrive at this conclusion. But when I had assembled my mental list of potential diagnoses, "nothing" was not among the options I had considered. I had become so accustomed to patients having problems warranting diagnosis and treatment that it had hardly occurred to me that a patient might come in to clinic with nothing the matter.

I was reminded of a time I attended a play, and partway through, the actors "took down the fourth wall" and began speaking directly to the audience. It was a bewildering experience, because all of the sudden, the normal rules of theater did not apply. This patient encounter left me feeling similarly disoriented.

The patient's urinalysis results came back a few minutes later, showing no abnormalities. The doctor and I reassured him that things appeared to be all right, and we sent him on his way.

14 January 2013

Blew it

The patient had come to the emergency room because over the course of an afternoon he had become short of breath, unable to walk more than a few feet. Now admitted to the hospital, while he was talking to me, he had to stop and take a breath after every third word.

I was meeting this patient as part of a teaching activity. The doctor who was caring for this patient was watching me as I took his history, performed a physical exam, and tried to work through the diagnosis.

When I was finished, the doctor and I went to the conference room and I was given the patient's EKG. "What's on your differential?" the doctor asked me.

I reasoned my way through several classes of disease that would cause shortness of breath: infection, left-sided heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive lung disease, and various types of lung disease. But none of these seemed to fit this patient's presentation.

"Keep going," he said. "You're missing something."

I racked my brain and came up with some esoteric diseases that were extremely unlikely.

"I'm thinking something big," he said.

I couldn't figure it out. "I give up," I said.

"Pulmonary embolism."

Shit! Pulmonary embolism is a common disease that can be life-threatening if unrecognized. And I hadn't recognized it, or even thought to look for signs of it on physical exam. This patient's presentation was classic, too.

As it turned out, the patient's lab results were inconsistent with pulmonary embolism, effectively ruling it out. But the awful feeling in my stomach remained. The obvious diagnosis hadn't made it onto my differential. This was the sort of mistake that could kill a patient.

Of course, I'm just a second-year medical student. I'm expected to make mistakes like this all the time. I will not be solely responsible for patients for quite a while. Even so, the teaching exercise was a rude reminder that there remains quite a lot for me to master.

I was meeting this patient as part of a teaching activity. The doctor who was caring for this patient was watching me as I took his history, performed a physical exam, and tried to work through the diagnosis.

When I was finished, the doctor and I went to the conference room and I was given the patient's EKG. "What's on your differential?" the doctor asked me.

I reasoned my way through several classes of disease that would cause shortness of breath: infection, left-sided heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive lung disease, and various types of lung disease. But none of these seemed to fit this patient's presentation.

"Keep going," he said. "You're missing something."

I racked my brain and came up with some esoteric diseases that were extremely unlikely.

"I'm thinking something big," he said.

I couldn't figure it out. "I give up," I said.

"Pulmonary embolism."

Shit! Pulmonary embolism is a common disease that can be life-threatening if unrecognized. And I hadn't recognized it, or even thought to look for signs of it on physical exam. This patient's presentation was classic, too.

As it turned out, the patient's lab results were inconsistent with pulmonary embolism, effectively ruling it out. But the awful feeling in my stomach remained. The obvious diagnosis hadn't made it onto my differential. This was the sort of mistake that could kill a patient.

Of course, I'm just a second-year medical student. I'm expected to make mistakes like this all the time. I will not be solely responsible for patients for quite a while. Even so, the teaching exercise was a rude reminder that there remains quite a lot for me to master.

07 January 2013

Money and medicine: career choices

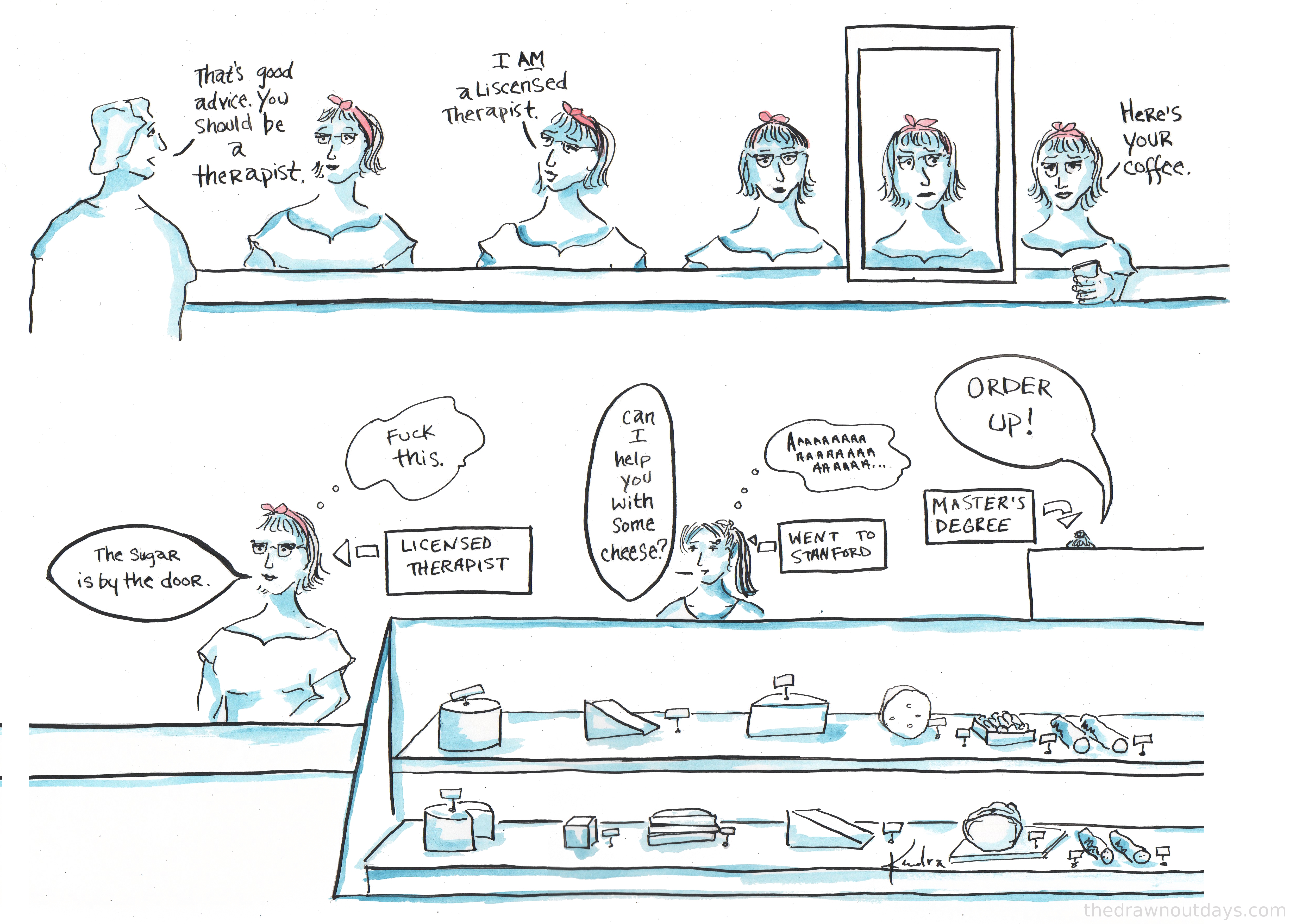

From "The Drawn Out Days," a Stanford graduate's ongoing series of drawings that chronicle her post-college life as a Brooklyn bartender and barista:

I went to a delightful potluck dinner where I was the only medical student (something of a rarity these days). The sun went down while we were eating, and after clearing the dishes we stretched out on the motley assortment of chairs, sofas, and pillows. In hushed tones, people started talking about their work situations. One had graduated with a degree in graphic design and could hardly find any work. Another had returned from a Fulbright fellowship and was unemployed. Several others had struck out looking for full-time employment. The job market is awful for people my age.

Their concerns felt a bit distant, because I'm still several years removed from the working world. But does being a medical student insulate oneself from the dispiriting economic realities of the day? It made me reflect upon how we choose our careers.

At the well-endowed university where I studied undergrad, at least a dozen professors knew me personally and were happy to meet with me and give career advice. There was also a well-staffed career advising center. For example, I stopped by the center to learn more about health professions. There I found an enormous binder of questionnaires filled out by alumni working in fields like medicine, podiatry, hospital administration, and epidemiology. Their write-ups included where they trained, why they find their work satisfying, what their average workday looks like, their salary range, what tips they have for undergraduates, etc. Many questionnaires also included contact info so that I could get in touch them and talk things over. Even with all of these resources available, I debated throughout my undergraduate years whether medical school was the right path for me.

Now I interact with undergraduates at other schools who have dramatically fewer career resources available to them. Sometimes they ask me for career advice. It unnerves me that some students I meet are basing their career choices on what I perceive as incomplete or inaccurate information.

And yet, can someone make a truly well-considered decision about whether becoming a physician is for them? It's hard to even figure out things like how much medical school will cost. Last year, Republicans in the House suddenly eliminated subsidized loans for medical students, meaning that new federal loans accrue interest during medical school and residency (at interest rates of 6.8% and 7.9%). This tacked on tens of thousands of dollars to the debt load that medical students will carry. Medical schools keep hiking tuition, and even the scholarships they offer students can be reduced or yanked after first year. It's increasingly common for students to graduate with over $200,000 in debt, financed at subprime interest rates. As that figure soars higher, it becomes increasingly difficult to cover interest payments and still make a dent in the loan principal.

Beyond the cost of education, the financial state of the profession is precarious. Medicare and private insurance reimbursement rates have been plummeting, and medical providers with substantially less training (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) are increasingly displacing doctors. If a student entering medical school today enters primary care, will he be able to pay off his loans within a reasonable timeframe? I can't make much of a prediction. Physicians are at the fickle mercy of legislators and private insurers. Furthermore, physicians' professional ethics and reluctance to organize leaves them particularly vulnerable to getting picked on.

And it's hard to know whether one will fit in the medical culture until one is in it. This field is extremely demanding. Some people get burned out. Some people realize it's not for them. Some people regret the specialty they train in. Some people get sick or injured and lack the physical stamina to proceed with their training. The thing is that once you've started, you can't really stop.

I don't have a good answer for the undergrads who seek my advice on whether to go into medicine. People will always need doctors, and doctors will always possess a unique means of serving their fellow man. But entering the medical profession is increasingly risky. It is a tremendous investment with uncertain reward. I hope for all of our sakes that it works out.

I went to a delightful potluck dinner where I was the only medical student (something of a rarity these days). The sun went down while we were eating, and after clearing the dishes we stretched out on the motley assortment of chairs, sofas, and pillows. In hushed tones, people started talking about their work situations. One had graduated with a degree in graphic design and could hardly find any work. Another had returned from a Fulbright fellowship and was unemployed. Several others had struck out looking for full-time employment. The job market is awful for people my age.

Their concerns felt a bit distant, because I'm still several years removed from the working world. But does being a medical student insulate oneself from the dispiriting economic realities of the day? It made me reflect upon how we choose our careers.

At the well-endowed university where I studied undergrad, at least a dozen professors knew me personally and were happy to meet with me and give career advice. There was also a well-staffed career advising center. For example, I stopped by the center to learn more about health professions. There I found an enormous binder of questionnaires filled out by alumni working in fields like medicine, podiatry, hospital administration, and epidemiology. Their write-ups included where they trained, why they find their work satisfying, what their average workday looks like, their salary range, what tips they have for undergraduates, etc. Many questionnaires also included contact info so that I could get in touch them and talk things over. Even with all of these resources available, I debated throughout my undergraduate years whether medical school was the right path for me.

Now I interact with undergraduates at other schools who have dramatically fewer career resources available to them. Sometimes they ask me for career advice. It unnerves me that some students I meet are basing their career choices on what I perceive as incomplete or inaccurate information.

Undergrad #1: "I was pre-med, but then Obamacare passed. It meant I would get paid so little if I became a doctor that I needed to switch careers. Now I'm planning to go into environmental law."

Me: "Lawyers coming out of law school are finding that it's a really tight job market. If money's an issue, are you sure that's the route you want to go?"

Undergrad #1: "Well, so long as I'm going to pick between sinking ships, I might as well do law."

___________

Undergrad #2: "I've been debating between med school and PA [physician assistant] school. As a PA I'd know about as much medicine as a doctor, but it's only 2 or 3 years of training."

Me: "Maybe this will be helpful for you when you're weighing your decision: I'm buddies with some PA students, and we find that PA school and medical school have pretty different aims. Becoming a physician involves learning medicine in much more depth and breadth than a PA, and that's why it takes so much longer to become a doctor."

Undergrad #2: "Yeah, but I really get medicine, so even if they don't teach us as much, I'm still going to learn it all."

And yet, can someone make a truly well-considered decision about whether becoming a physician is for them? It's hard to even figure out things like how much medical school will cost. Last year, Republicans in the House suddenly eliminated subsidized loans for medical students, meaning that new federal loans accrue interest during medical school and residency (at interest rates of 6.8% and 7.9%). This tacked on tens of thousands of dollars to the debt load that medical students will carry. Medical schools keep hiking tuition, and even the scholarships they offer students can be reduced or yanked after first year. It's increasingly common for students to graduate with over $200,000 in debt, financed at subprime interest rates. As that figure soars higher, it becomes increasingly difficult to cover interest payments and still make a dent in the loan principal.

Beyond the cost of education, the financial state of the profession is precarious. Medicare and private insurance reimbursement rates have been plummeting, and medical providers with substantially less training (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) are increasingly displacing doctors. If a student entering medical school today enters primary care, will he be able to pay off his loans within a reasonable timeframe? I can't make much of a prediction. Physicians are at the fickle mercy of legislators and private insurers. Furthermore, physicians' professional ethics and reluctance to organize leaves them particularly vulnerable to getting picked on.

And it's hard to know whether one will fit in the medical culture until one is in it. This field is extremely demanding. Some people get burned out. Some people realize it's not for them. Some people regret the specialty they train in. Some people get sick or injured and lack the physical stamina to proceed with their training. The thing is that once you've started, you can't really stop.

I don't have a good answer for the undergrads who seek my advice on whether to go into medicine. People will always need doctors, and doctors will always possess a unique means of serving their fellow man. But entering the medical profession is increasingly risky. It is a tremendous investment with uncertain reward. I hope for all of our sakes that it works out.

02 January 2013

Diagnosis III

A longtime patient had come in complaining of progressive fatigue, weakness, and numbness in her hands and feet. Her primary-care physician and I were taking a few seconds to skim her medical chart before we stopped by her room to examine her.

I glanced at the patient's weight and noticed that she was borderline obese. A potential diagnosis came together in my mind. "Has this patient ever had gastric bypass surgery?" I asked.

Him: "No."

Me: "Darn."

Him: "Why do you ask?"

Me: "I was wondering if maybe she has a vitamin deficiency, like B12, that's causing her symptoms." Some types of gastric bypass, such as Roux-en-Y procedures, remove some of the small intestine, thus reducing absorption of certain critical vitamins. Patients are supposed to take hefty vitamin supplements for life as a result.

Him: "It was a nice thought."

We went in to see the patient. She was very unhappy because she felt like she had no energy. Her family and job were stressful. And she was disappointed with her weight. "Even after getting that gastric bypass, I still weigh too much."

The doctor's eyes lit up. "How long ago was your gastric bypass?" he asked.

"It happened maybe 4 years back," the patient responded.

"I assume after your procedure they prescribed a special mega-vitamin."

"Yeah, but I didn't like it. I stopped taking it maybe half a year ago."

I couldn't stop myself from grinning.

Although I'm not skilled enough to be seeing patients entirely on my own, sometimes I've been able to make diagnoses that the doctors I'm with have overlooked. Part of the reason is that my training is uneven. In medical school, we spend a lot of time learning diseases that are rarely encountered in clinical practice. We also have seen so few patients that we have little sense of what is common and what is uncommon, which diseases make sense and which ones don't. When I see a patient, the list of diseases I'm considering differs from that of a seasoned physician.

But sometimes the patient doesn't have the disease a seasoned physician expects, and these are the times I get to shine. Sometimes, two minds are better than one. I wouldn't have expected it, but I think that patients get better care when they are examined by both a physician and a medical student as opposed to only a physician.

I glanced at the patient's weight and noticed that she was borderline obese. A potential diagnosis came together in my mind. "Has this patient ever had gastric bypass surgery?" I asked.

Him: "No."

Me: "Darn."

Him: "Why do you ask?"

Me: "I was wondering if maybe she has a vitamin deficiency, like B12, that's causing her symptoms." Some types of gastric bypass, such as Roux-en-Y procedures, remove some of the small intestine, thus reducing absorption of certain critical vitamins. Patients are supposed to take hefty vitamin supplements for life as a result.

Him: "It was a nice thought."

We went in to see the patient. She was very unhappy because she felt like she had no energy. Her family and job were stressful. And she was disappointed with her weight. "Even after getting that gastric bypass, I still weigh too much."

The doctor's eyes lit up. "How long ago was your gastric bypass?" he asked.

"It happened maybe 4 years back," the patient responded.

"I assume after your procedure they prescribed a special mega-vitamin."

"Yeah, but I didn't like it. I stopped taking it maybe half a year ago."

I couldn't stop myself from grinning.

Although I'm not skilled enough to be seeing patients entirely on my own, sometimes I've been able to make diagnoses that the doctors I'm with have overlooked. Part of the reason is that my training is uneven. In medical school, we spend a lot of time learning diseases that are rarely encountered in clinical practice. We also have seen so few patients that we have little sense of what is common and what is uncommon, which diseases make sense and which ones don't. When I see a patient, the list of diseases I'm considering differs from that of a seasoned physician.

But sometimes the patient doesn't have the disease a seasoned physician expects, and these are the times I get to shine. Sometimes, two minds are better than one. I wouldn't have expected it, but I think that patients get better care when they are examined by both a physician and a medical student as opposed to only a physician.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)