I went to a delightful potluck dinner where I was the only medical student (something of a rarity these days). The sun went down while we were eating, and after clearing the dishes we stretched out on the motley assortment of chairs, sofas, and pillows. In hushed tones, people started talking about their work situations. One had graduated with a degree in graphic design and could hardly find any work. Another had returned from a Fulbright fellowship and was unemployed. Several others had struck out looking for full-time employment. The job market is awful for people my age.

Their concerns felt a bit distant, because I'm still several years removed from the working world. But does being a medical student insulate oneself from the dispiriting economic realities of the day? It made me reflect upon how we choose our careers.

At the well-endowed university where I studied undergrad, at least a dozen professors knew me personally and were happy to meet with me and give career advice. There was also a well-staffed career advising center. For example, I stopped by the center to learn more about health professions. There I found an enormous binder of questionnaires filled out by alumni working in fields like medicine, podiatry, hospital administration, and epidemiology. Their write-ups included where they trained, why they find their work satisfying, what their average workday looks like, their salary range, what tips they have for undergraduates, etc. Many questionnaires also included contact info so that I could get in touch them and talk things over. Even with all of these resources available, I debated throughout my undergraduate years whether medical school was the right path for me.

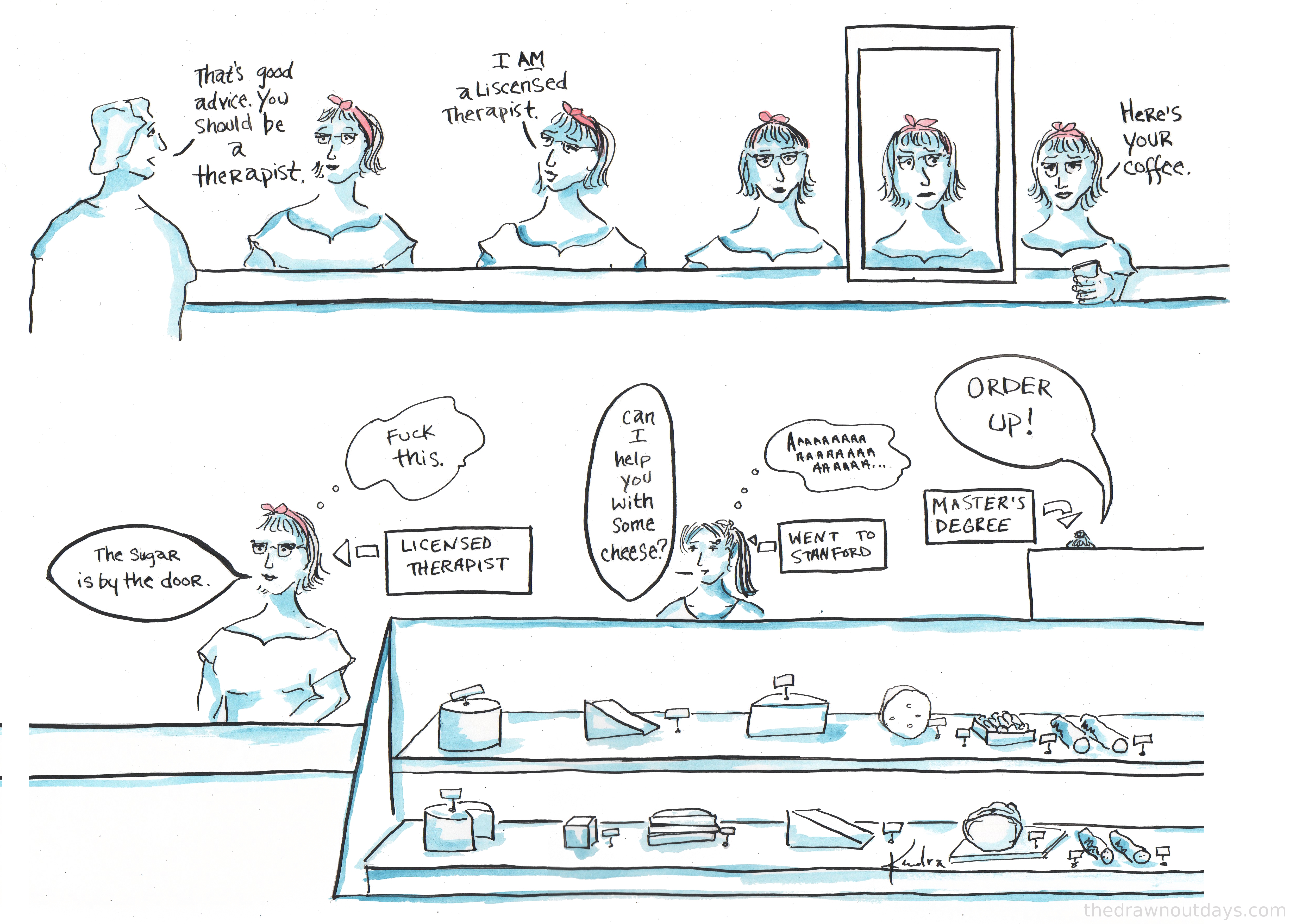

Now I interact with undergraduates at other schools who have dramatically fewer career resources available to them. Sometimes they ask me for career advice. It unnerves me that some students I meet are basing their career choices on what I perceive as incomplete or inaccurate information.

Undergrad #1: "I was pre-med, but then Obamacare passed. It meant I would get paid so little if I became a doctor that I needed to switch careers. Now I'm planning to go into environmental law."

Me: "Lawyers coming out of law school are finding that it's a really tight job market. If money's an issue, are you sure that's the route you want to go?"

Undergrad #1: "Well, so long as I'm going to pick between sinking ships, I might as well do law."

___________

Undergrad #2: "I've been debating between med school and PA [physician assistant] school. As a PA I'd know about as much medicine as a doctor, but it's only 2 or 3 years of training."

Me: "Maybe this will be helpful for you when you're weighing your decision: I'm buddies with some PA students, and we find that PA school and medical school have pretty different aims. Becoming a physician involves learning medicine in much more depth and breadth than a PA, and that's why it takes so much longer to become a doctor."

Undergrad #2: "Yeah, but I really get medicine, so even if they don't teach us as much, I'm still going to learn it all."

And yet, can someone make a truly well-considered decision about whether becoming a physician is for them? It's hard to even figure out things like how much medical school will cost. Last year, Republicans in the House suddenly eliminated subsidized loans for medical students, meaning that new federal loans accrue interest during medical school and residency (at interest rates of 6.8% and 7.9%). This tacked on tens of thousands of dollars to the debt load that medical students will carry. Medical schools keep hiking tuition, and even the scholarships they offer students can be reduced or yanked after first year. It's increasingly common for students to graduate with over $200,000 in debt, financed at subprime interest rates. As that figure soars higher, it becomes increasingly difficult to cover interest payments and still make a dent in the loan principal.

Beyond the cost of education, the financial state of the profession is precarious. Medicare and private insurance reimbursement rates have been plummeting, and medical providers with substantially less training (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) are increasingly displacing doctors. If a student entering medical school today enters primary care, will he be able to pay off his loans within a reasonable timeframe? I can't make much of a prediction. Physicians are at the fickle mercy of legislators and private insurers. Furthermore, physicians' professional ethics and reluctance to organize leaves them particularly vulnerable to getting picked on.

And it's hard to know whether one will fit in the medical culture until one is in it. This field is extremely demanding. Some people get burned out. Some people realize it's not for them. Some people regret the specialty they train in. Some people get sick or injured and lack the physical stamina to proceed with their training. The thing is that once you've started, you can't really stop.

I don't have a good answer for the undergrads who seek my advice on whether to go into medicine. People will always need doctors, and doctors will always possess a unique means of serving their fellow man. But entering the medical profession is increasingly risky. It is a tremendous investment with uncertain reward. I hope for all of our sakes that it works out.